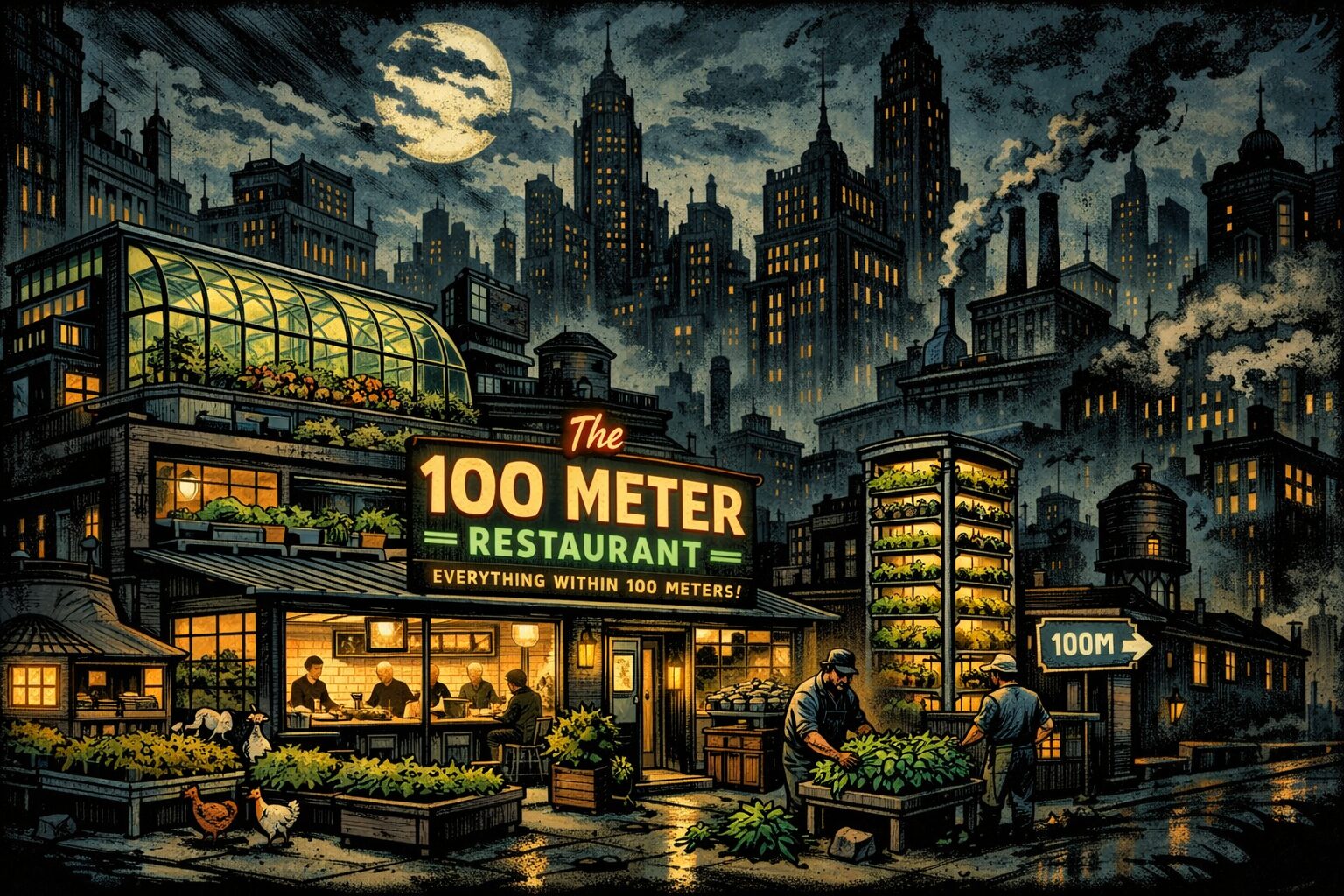

The idea of a 100-meter restaurant is deceptively simple. Every ingredient served must originate from within a strict 100-meter radius of the kitchen. Not locally inspired, not regionally sourced, but physically bound to immediate surroundings. Rooftops, basements, courtyards, neighboring buildings. Nothing beyond that line. No imported oil, no salt from afar, no coffee, no spices tied to other climates. Only what grows, lives, or can be transformed within that narrow perimeter.

In an era where “local” has become a flexible marketing term, the 100-meter concept introduces an uncompromising definition of proximity. It turns geography from narrative into rule. The appeal is obvious: radical transparency, extreme sustainability, and a story guests can literally walk through. Yet the same rigidity that gives the concept its power also exposes its fragility. This report examines the 100-meter restaurant not as a pop-up idea or artistic provocation, but as a hypothetical operating model under real-world conditions. The goal is to understand what such a restaurant could realistically produce, how it would need to function economically, and why its limits may ultimately define its relevance.

Trend Snapshot

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trend Name | 100-Meter Restaurant |

| Key Components | Ultra-local sourcing, on-site production, closed systems |

| Spread | Extremely limited, concept-driven |

| Examples | Relæ, Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Silo |

| Social Media | Process transparency, origin storytelling |

| Demographics | Urban, affluent, sustainability-focused |

| Wow Factor | Absolute traceability |

| Trend Phase | Conceptual, structurally constrained |

Defining Radical Proximity Beyond “Local”

Most restaurants that claim local sourcing still rely on distance. Even the most conscientious farm-to-table operations depend on regional logistics, seasonal imports, and wholesale infrastructure. The 100-meter model removes these buffers entirely. There is no fallback supplier, no emergency delivery, no seasonal workaround. What exists within the boundary defines the menu. What does not exist is excluded by default.

This distinction is crucial. The concept is often confused with restaurants that emphasize close relationships with farmers or that operate on large rural estates. Those models shorten supply chains but do not eliminate them. A strict 100-meter rule, by contrast, collapses sourcing and production into a single site. The restaurant becomes not just a place of transformation but a place of origin.

Historically, only a handful of restaurants have approached this level of constraint. Relæ pushed locality aggressively by reducing supplier distance and eliminating unnecessary imports. Blue Hill at Stone Barns integrated farm and kitchen on an unprecedented scale, though with access to extensive land. Silo focused on zero-waste systems and in-house processing rather than strict distance. None of these operate under a literal 100-meter constraint in dense urban environments. That gap matters, because density is where the concept becomes most revealing.

Urban Density as the Ultimate Constraint

Cities are not designed for self-sufficiency. They exist because food, materials, and energy can be moved efficiently across distance. The 100-meter restaurant challenges this logic directly. It asks whether a hospitality business can function when logistics are replaced by architecture and biology.

In dense cities, the available productive surface is fragmented. Rooftops are limited and often structurally constrained. Basements offer space but little natural light. Courtyards are rare and shared. Even when controlled-environment agriculture is introduced, yields are finite. Leafy greens and herbs can be grown reliably, but they cannot scale infinitely. Every additional seat in the dining room increases pressure on a system that cannot expand without physical space.

New York is a useful hypothetical example precisely because it amplifies these tensions. The city has proven that rooftop farming and indoor growing are technically viable, as seen in large-scale urban agriculture projects. Yet those systems succeed because they are integrated into broader supply networks, not because they operate in isolation. A 100-meter restaurant would remove that integration by design. What remains is a closed loop with little margin for error.

What Production Looks Like Inside the Boundary

Under current technology, the productive capacity of a 100-meter radius is uneven. Certain categories thrive under constraint. Leafy greens, herbs, and microgreens perform well in hydroponic or soil-based systems and mature quickly. Mushrooms offer high yield relative to space and provide depth of flavor that can partially replace animal protein. Fermentation extends shelf life and creates acidity and complexity without relying on citrus or imported vinegar.

Other categories reveal the limits of the model. Root vegetables require depth and time, making them inefficient. Fruit crops are energy-intensive and unpredictable indoors. Grains are effectively nonviable at meaningful scale. Protein production presents ethical, regulatory, and spatial challenges. Aquaponics introduces complexity that few restaurant operations can sustain. Insect farming is efficient but culturally marginal in many dining contexts.

Equally important are the structural absences. Salt does not exist in most urban environments. Oils require large volumes of seeds or fruit. Coffee, tea, cocoa, spices, and sugar are tied to specific climates. A strict 100-meter restaurant must therefore abandon these ingredients entirely or replace them with functional substitutes derived from local processes. This is not a creative choice but a material consequence of the rule.

Menu Design Under Structural Scarcity

A 100-meter menu would be defined less by creativity than by repetition. Growth cycles dictate availability. Harvest timing shapes service. Dishes recur with minor variation rather than rotating constantly. Choice is limited, and that limitation must be framed as intentional rather than deficient.

Typical menus would be plant-forward by necessity. Greens, mushrooms, and preserved vegetables form the backbone of most courses. Fermentation provides acidity and depth where citrus and spices are absent. Sweetness, when present, comes from vegetable reduction or limited fruit harvests rather than refined sugar. Beverages follow similar logic: infusions and ferments replace coffee, tea, and imported alcohol.

For guests, the experience shifts from abundance to coherence. Satisfaction comes from understanding why a dish exists, not from recognizing its components. This requires a different contract between restaurant and diner, one built on education and trust rather than expectation.

Business Reality Versus Conceptual Appeal

From a business perspective, the 100-meter restaurant is structurally disadvantaged. Real estate costs remain fixed while seating capacity shrinks. Labor costs increase as staff take on agricultural and preservation roles alongside service. Energy consumption rises with controlled-environment systems. Supply risk moves in-house, where crop failure directly affects revenue.

Revenue potential is capped by biology. Unlike conventional restaurants, volume cannot simply be increased through demand. Pricing must therefore compensate for scarcity, pushing the model toward high-end positioning, limited seatings, and advance reservations. Even then, margins remain fragile.

According to Modern Restaurant Management, supply-chain efficiency is a critical factor in restaurant profitability, and disruptions or inefficiencies significantly increase operational risk¹. A 100-meter restaurant intentionally abandons many of these efficiencies. As a result, long-term viability depends heavily on ownership structure, patient capital, and alignment between financial expectations and philosophical goals.

Transparency as the Core Value Proposition

Where the model gains strength is transparency. Guests increasingly value clear origin stories and visible production systems. Produce Leaders notes a growing consumer emphasis on understanding where food comes from and how it is produced, particularly in urban markets². A 100-meter restaurant offers absolute clarity. There are no distant suppliers, no abstract claims, no hidden trade-offs.

This transparency becomes the primary luxury. Menus reference rooms instead of regions. Servers explain growth cycles rather than provenance. The restaurant becomes legible in a way few others are. For a specific audience, this clarity justifies both price and limitation.

A Realistic Conclusion

The 100-meter restaurant is theoretically possible under current conditions, but only within narrow parameters. It requires purpose-designed spaces, aligned ownership, limited scale, and guests willing to accept absence as part of the experience. It is not scalable, resilient, or easily replicable. Its value lies not in replacing existing models but in testing their assumptions.

By pushing locality to its physical limit, the concept exposes how dependent modern dining is on distance. It reveals which ingredients, processes, and expectations are structural rather than optional. In doing so, it points toward more viable hybrids: models that maintain a hyper-local core while acknowledging the necessity of regional support.

The 100-meter restaurant is not a solution. It is a boundary. And boundaries, when examined closely, tend to teach more than blueprints.

Sources

- Modern Restaurant Management – Bridging Farm-to-Table Expectations with Supply Chain Realities

https://modernrestaurantmanagement.com/bridging-the-farm-to-table-expectations-with-supply-chain-realities/ - Produce Leaders – The Growing Consumer Emphasis on Where Their Food Comes From

https://www.produceleaders.com/the-growing-consumer-emphasis-on-where-their-food-comes-from/