When we talk about historical food trends, we often think of spice routes, royal banquets, or the rise of coffeehouses. But few know that, for over 200 years, Europe embraced a culinary-medical practice that today sounds unthinkable: eating human remains. Not out of desperation, but as a form of therapy — and it was wildly popular.

From powdered skulls in apothecaries to blood-infused elixirs at royal courts, consuming human flesh and fluids wasn’t taboo — it was treatment. Across social classes and regions, people ingested parts of the dead to cure everything from headaches to epilepsy. At the same time, Europeans condemned the ritual cannibalism of Indigenous peoples, using it to justify colonial violence — a chilling irony.

Trend Snapshot

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Name & Definition | Medicinal Cannibalism – consuming human body parts as therapeutic remedies |

| Key Components | Blood, fat, skull powder, flesh from mummies |

| Where Popular | Germany, France, Italy, England (16th–18th century) |

| Notable Examples | Mumia vera in pharmacies; skull elixirs in English courts |

| Social Media | None — but heavily documented in medical treatises and recipe books |

| Target Audience | All classes — from nobles to commoners |

| Wow Factor | Human flesh was considered an actual superfood |

| Trend Status | Obsolete since 18th century, but once mainstream |

A Trend Born from Trauma and Belief

Europe’s fascination with human-based remedies surged during the 16th century. As plague, war, and poor sanitation ravaged populations, people turned to what they believed was the most potent cure available: the human body itself.

“Over a period of 200 years, both rich and poor, educated and illiterate Europeans routinely engaged in medicinal cannibalism,” notes historian David Castleton. Far from being a fringe practice, it was a widespread belief deeply embedded in the medical mainstream. Physicians recommended it, apothecaries stocked it, and patients demanded it.

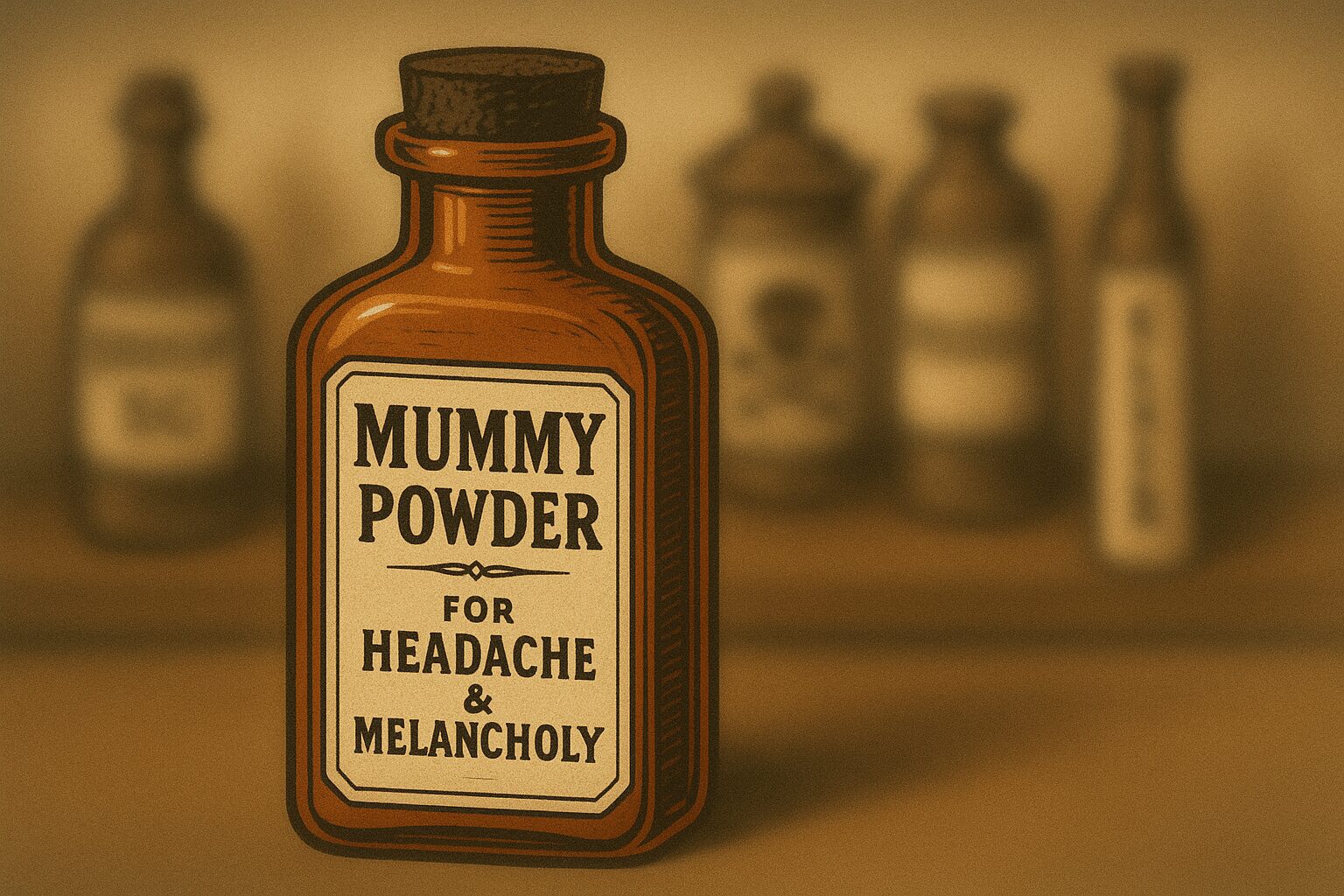

The most iconic product? Mumia vera — a powder made from ground-up Egyptian mummies. It was imported across Europe and believed to hold spiritual and curative powers, especially for internal bleeding or bruising. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, demand for mumia was so high that grave robbing became a transcontinental business.

What Was Actually Consumed

While the idea of “eating people” sounds shocking today, the reality was often less dramatic — but no less disturbing. Apothecaries sold:

- Dried flesh from mummies

- Powdered skulls (sometimes from European corpses)

- Human fat, used in balms for arthritis

- Fresh blood, often taken from executed prisoners and drunk on the spot

These were mixed into tinctures, ointments, and even sweets. Recipes weren’t secret; they were printed in official medical books of the time.

In England, “King’s Drops” — a tincture made from skull and alcohol — were a common prescription. German and French doctors likewise used human-derived remedies for epilepsy, headaches, and even love sickness.

Not Just for the Elite

Unlike exotic spices or luxury goods, corpse medicine was available to everyone. While kings and aristocrats had personal physicians blending custom formulas, commoners could purchase simpler versions in their local pharmacy. Some were administered by midwives or monks. In poorer regions, people would even gather soil soaked with blood from execution sites, believing it contained healing power.

Medicinal cannibalism was not cloaked in secrecy. It was as normalized as leeches or mercury. And that normalization ran deep — across class lines, regions, and even religions.

The Hypocrisy of Civilized Europe

While European doctors ground up skulls in laboratories, these same societies accused Indigenous peoples of barbarism for practicing ritual cannibalism. The double standard is glaring.

In many Indigenous cultures, consuming parts of the dead — especially in broth — was a spiritual act. Children in some South American tribes were fed small portions of deceased relatives to “keep them in the family,” as noted in a comparative study on mortuary cannibalism. Far from being violent, these acts were mourning rituals, embedded with meaning and respect.

In contrast, Europe turned death into commerce. Bodies were stolen, bought, and sold — sometimes against the wishes of families — to feed a market hungry for cures. The same colonizing powers that justified conquest by pointing to “savage practices” at home practiced something arguably more dehumanizing: commodified cannibalism.

How the Trend Died Out

By the 18th century, the winds of science and Enlightenment began to change things. As anatomy and biology advanced, faith in corpse-based cures waned. The public, too, became uneasy. Even without modern ethics, people began to question whether ingesting the dead might be not only ineffective — but dangerous or immoral.

New medications, better hygiene, and the gradual professionalization of medicine finally pushed corpse consumption out of mainstream practice. By the 1800s, only fringe alchemists and rural quacks still used it.

Yet its legacy remains. Medicinal cannibalism isn’t a footnote — it’s a central chapter in Europe’s medical and culinary history. And it reminds us that not all food trends age well.

Conclusion: When Healing Becomes Haunting

The story of medicinal cannibalism is not just about shocking practices — it’s about how belief, fear, and desperation can reshape what a culture considers edible. It forces us to confront the blurred lines between food, medicine, and morality. And it’s a reminder that today’s norms may one day seem just as strange.

And for a deeper look into the emotional pull of comfort foods, don’t miss Carb Comeback: What the Global Appetite for Starch Says About Us.