As ultra-processed foods and lab-grown alternatives dominate headlines, a counter-movement is emerging—one that looks backward to move forward. Around the world, chefs, food innovators, and sustainability-minded consumers are rediscovering Indigenous culinary wisdom as a blueprint for the future of food. These traditions, shaped over thousands of years, reflect symbioses with land, climate, and culture. Today, they are influencing fine dining, regenerative agriculture, fermentation trends, and the broader conversation about what responsible eating looks like. From native grains and wild herbs to nomadic dairy fermentations and ancestral agricultural systems, Indigenous foodways are helping define the next decade of gastronomic innovation. This article explores how these ancient knowledge systems are informing the future—globally, strategically, and deliciously.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trend Name | Indigenous foodways: ancestral culinary traditions rooted in ecology, culture, and sustainability |

| Key Components | Local wild foods, heritage grains, native proteins, fermentation, foraged produce |

| Spread | Fine dining, pop-ups, food festivals, Indigenous-owned ventures |

| Examples | Cosme NYC, Attica Melbourne, Noma Copenhagen, KOKS Faroe Islands, Owamni Minneapolis |

| Social Media | #IndigenousCuisine, #NativeFoods, #RegenerativeFood, #ForagedFlavors |

| Demographics | Conscious foodies, chefs, sustainability advocates, Gen Z, cultural preservationists |

| Wow Factor | Deep environmental synergy, nutrient-rich heritage ingredients, culturally embedded techniques |

| Trend Phase | Emerging to peak |

The Wisdom of Ancestral Eating

Across continents, Indigenous communities have honed culinary systems that reflect deep relationships with land and ecology. These systems evolved not through industrial optimisation but through long-term observation of landscapes, seasons, and the behaviour of native plants and animals. Unlike modern food systems, which often prioritise scale over sustainability, ancestral foodways seek balance: they work with climate, not against it; they protect biodiversity rather than diminish it; and they centre cultural meaning as much as nutrition.

In many Indigenous food traditions, wild foods form the backbone of culinary identity. These include wild greens, nuts, tubers, berries, mushrooms, and small game. They are harvested with cultural rules that prevent depletion, build soil health, and sustain local ecosystems. According to MDPI, Indigenous food systems safeguard biodiversity while sustaining cultural identity, demonstrating a model where environmental balance and nutritional adequacy reinforce each other. This approach is resonating globally as chefs and conscious consumers look for food experiences that feel meaningful, rooted, and regenerative.

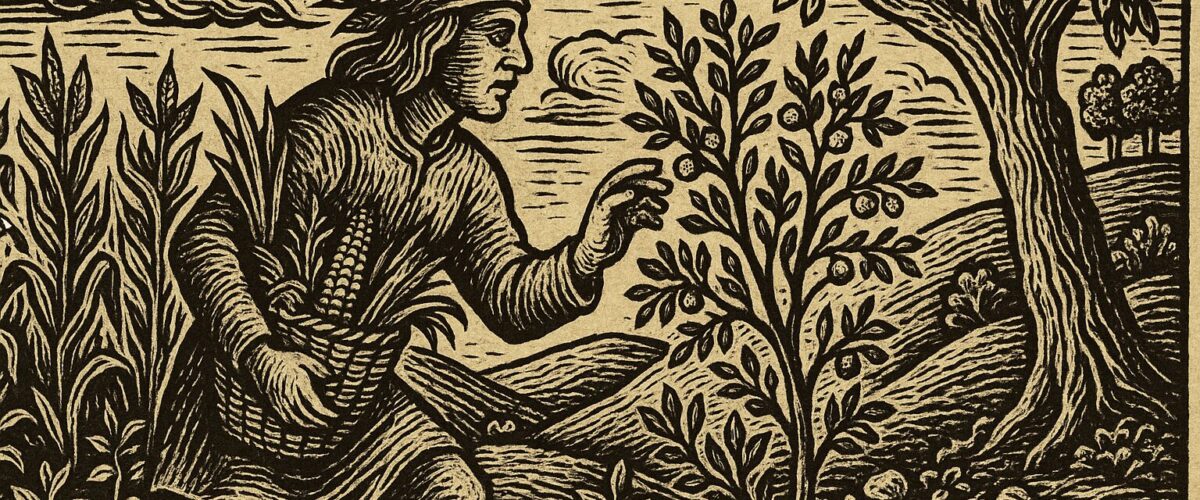

Indigenous Foodways

Ancestral culinary systems rooted in ecology, culture, and sustainability are stepping onto centre stage – from fine dining tasting menus to chef-driven pop-ups and R&D labs.

Fermentation is another backbone of ancestral eating, from Africa’s fermented grains to the Arctic’s preserved fish. These methods were born from necessity but evolved into culinary cornerstones. Their resurgence aligns with global interest in gut health, natural preservation, and low-waste food processing. Indigenous fermentation techniques often use wild microbes and rely on ambient conditions, creating flavours and textures impossible to replicate industrially.

Sustainability advocates increasingly recognise the value embedded in ancestral practices. As contemporary food industries struggle with climate impact, monoculture vulnerability, and declining soil fertility, Indigenous systems offer a blueprint for resilient, place-based food production. They show that looking back is not regression—it is innovation rooted in context.

From Milpa to Masa Madre: Latin America’s Corn Comeback

Few ingredients reveal the depth of Indigenous food systems like corn in Mesoamerica. For thousands of years, communities have grown maize not in isolation but as part of the Milpa system—a biodiverse polyculture that pairs corn, beans, and squash. This trio works symbiotically: beans fix nitrogen into the soil, squash provides ground cover to retain moisture, and corn creates vertical structure for the beans to climb. The system is a masterclass in regenerative agriculture long before the term existed.

Today, chefs and food entrepreneurs are reconnecting with heirloom maize varieties, including blue, red, purple, and speckled corns that carry distinct flavours and nutritional profiles. At restaurants like Cosme in New York City, ancestral preparation techniques—nixtamalisation, stone-grinding, and slow fermentation—take centre stage. These practices elevate corn from commodity to cultural artefact.

Nixtamalisation, an ancient method using alkaline water, unlocks amino acids, enhances digestibility, and deepens flavour. It illustrates how Indigenous food science contains layers of biochemical insight. As diners become more knowledgeable about how food interacts with the body, these traditional techniques gain new relevance.

Heritage corn also anchors identity. Its revival strengthens farming communities that steward rare seeds, many of which are threatened by monoculture agriculture. In Berlin, small restaurants and pop-ups showcase native maize in tacos, tamales, and masa-based breads, emphasising terroir and Indigenous agricultural lineage. The modern reinterpretation of these traditions bridges ancestral memory with contemporary creativity.

Bushfoods on the White Tablecloth: Australia’s Edible Heritage

Australia’s Indigenous food culture is one of the oldest on Earth, yet it is only recently gaining mainstream culinary recognition. Ingredients such as Wattleseed, Finger Lime, Saltbush, Lemon Myrtle, and Kakadu Plum have long played central roles in Aboriginal diets, offering nutrition tailored to arid landscapes and variable climates.

The transition of these ingredients into fine dining brings both opportunity and responsibility. At Attica in Melbourne, chef Ben Shewry collaborates with Indigenous growers and knowledge holders to highlight native flavours in a respectful, equitable manner. Bushfoods appear in tasting menus not as novelties but as essential expressions of place.

Kakadu Plum, one of the highest natural sources of vitamin C, is used in condiments and desserts to bring acidity and brightness. Wattleseed, with its coffee-chocolate aroma, anchors savoury and sweet dishes alike. Finger Lime pearls add citrus complexity, and Saltbush grounds dishes with herbal salinity.

Yet this rise prompts crucial conversations around cultural attribution, economic participation, and ethical sourcing. Indigenous communities must remain active beneficiaries—culturally, economically, and narratively. Restaurants at the forefront of this movement highlight origin stories, farmer partnerships, and the cultural significance of each ingredient. This reflects a deeper alignment with Indigenous values: reciprocity, respect, and responsibility.

As climate change accelerates, the adaptive nature of bushfoods—built for drought, heat, and nutrient-poor soils—makes them particularly relevant. Their growing global interest supports the idea that Indigenous systems hold answers to contemporary environmental instability.

Nordic Lessons: What Sami Food Taught New Nordic Cuisine

Scandinavia’s famed culinary renaissance, often associated with Noma and New Nordic Cuisine, draws heavily from Indigenous Sami food traditions of Arctic Lapland. Long before chefs in Copenhagen championed seasonality and foraging, Sami communities practiced them out of ecological necessity.

Reindeer, wild berries, lichen, herbs, freshwater fish, and preserved meats form the backbone of Sami cuisine. Fermentation, drying, smoking, and curing helped communities survive long winters. These techniques now underpin some of the world’s most admired cooking philosophies.

Restaurants such as KOKS in the Faroe Islands incorporate Arctic preservation methods, creating menus that echo Sami principles of resourcefulness and reverence. The embrace of “hyper-locality” in New Nordic cuisine is a direct reflection of Indigenous cooking within Arctic landscapes—where every ingredient must be respected, valued, and used with intention.

This influence has sparked debates around cultural appropriation versus cultural appreciation. But the larger truth is undeniable: Indigenous Arctic knowledge has shaped some of the most influential food movements of the past decade. Without understanding these roots, the global narrative of “Nordic innovation” remains incomplete.

The Native American Food Renaissance

Across North America, Indigenous chefs are reviving pre-colonial cuisines as acts of cultural preservation, health restoration, and creative exploration. These foodways emphasise native grains, wild proteins, berries, roots, and seasonal plants that sustained communities for centuries.

Dishes avoid wheat, dairy, and cane sugar, focusing instead on ingredients like bison, corn, wild rice, squash, chokecherries, pine, maple, and freshwater fish. This ingredient set reflects ecosystems with immense biodiversity and culinary potential.

Owamni in Minneapolis, led by chef Sean Sherman, has become a global symbol of this renaissance. Its menu showcases foods free from colonial influences, demonstrating that Indigenous cuisine is both ancient and contemporary. Meanwhile, chef David Wolfman in Canada uses media and education to spotlight game meats, foraged herbs, and traditional cooking techniques, reconnecting diners to Indigenous culinary legacies.

These efforts extend beyond restaurants. Food sovereignty programs support community gardens, seed banks, and youth education initiatives, reviving local food systems disrupted by colonisation. As interest grows, Indigenous ingredients like wild rice and bison gain traction in retail and speciality markets, creating opportunities for cultural and economic renewal.

According to Interesjournals, Indigenous foods offer nutrient density and environmental resilience, making them valuable for modern diets. Their revival aligns with global priorities around health, sustainability, and cultural preservation.

Nomadic Know-How: African Grains and Fermented Dairy in the Spotlight

Among Africa’s nomadic and pastoral communities, food traditions reflect mobility, resource efficiency, and environmental wisdom. Groups such as the Fulani, Tuareg, Tigrayans, and Berber have developed fermentation systems and grain cultivation practices suited to drought, heat, and scarce resources.

Fermented dairy—such as fura da nono, gariss, and ergo—offers nutrient security in harsh climates. These products are microbiologically dynamic, rich in probiotics, and made with minimal inputs. They fit seamlessly into the global movement toward fermented foods and gut-friendly diets.

Climate-resilient grains such as fonio, teff, and pearl millet illustrate deep Indigenous adaptation to difficult landscapes. Fonio, one of West Africa’s oldest cereals, matures quickly, grows in poor soils, and holds significant cultural importance. Teff, the foundation of Ethiopian injera, is uniquely nutritious and versatile.

Chefs and food entrepreneurs are now bringing these grains into global markets. Their rise intersects with larger sustainability conversations: they support soil health, require minimal water, and encourage agricultural diversity. This relevance intensifies as climate pressures reshape global grain economics.

By adopting nomadic food knowledge, the global industry gains access to ancient strategies for resilience, nutrition, and flavour innovation. These are not trend ingredients—they are longstanding solutions waiting to be recognised.

Ancient Flavours for a Future-Ready Table

Indigenous food traditions are not relics; they are dynamic systems with solutions for modern challenges. Their wisdom offers pathways toward biodiversity, soil regeneration, food sovereignty, and cultural continuity. As chefs, researchers, and consumers embrace these traditions, the global food industry shifts from extractive models toward regenerative ones.

Indigenous foodways remind us that deliciousness and sustainability need not be opposing goals. They show that innovation often starts with remembering—and that the future of food may be rooted in the past.

For further exploration on Africa’s contribution to global food culture, see the article

Can African Cuisine Become the Next Global Food Trend?